The Rise of Diversity and Population

Terminology in Biomedical Research

This website was designed to serve as supplement to a paper in progress on the rise of diversity in biomedical research. While the motivation and methods are outlined below, our findings can be found by clicking the Results tab above.

Overview

Recent scholarship has highlighted the rise of “diversity projects” across various educational and business contexts, but few studies have explored the meaning of diversity in biomedical research. In this paper, we employ computational text analysis to examine quantitative trends in the use of various forms of diversity and population terminology in a sample of ~2.5 million biomedical abstracts spanning a 30-year period. Our analyses demonstrate marked growth in sex/gender, lifecourse, and socio-economic terms while terms relating to race/ethnicity have largely plateaued or declined in usage since the mid-2000s. The use of diversity as well as national, continental, and subcontinental population labels have grown dramatically over the same period. To better understand the relations between these terms, we use word embeddings to study the semantic similarity between the use of diversity and racial/ethnic terminology. Our results reveal that diversity has become less similar to racial/ethnic terms while becoming more similar to sex/gender, sexuality, and national terms used to describe countries in the Global South. Taken together, this work shows that diversity in biomedical research is becoming increasingly decoupled from discussions of social inequity and instead operates to describe human populations based on geographical labeling rather than racial or ethnic classifiers.

Data/Methodology

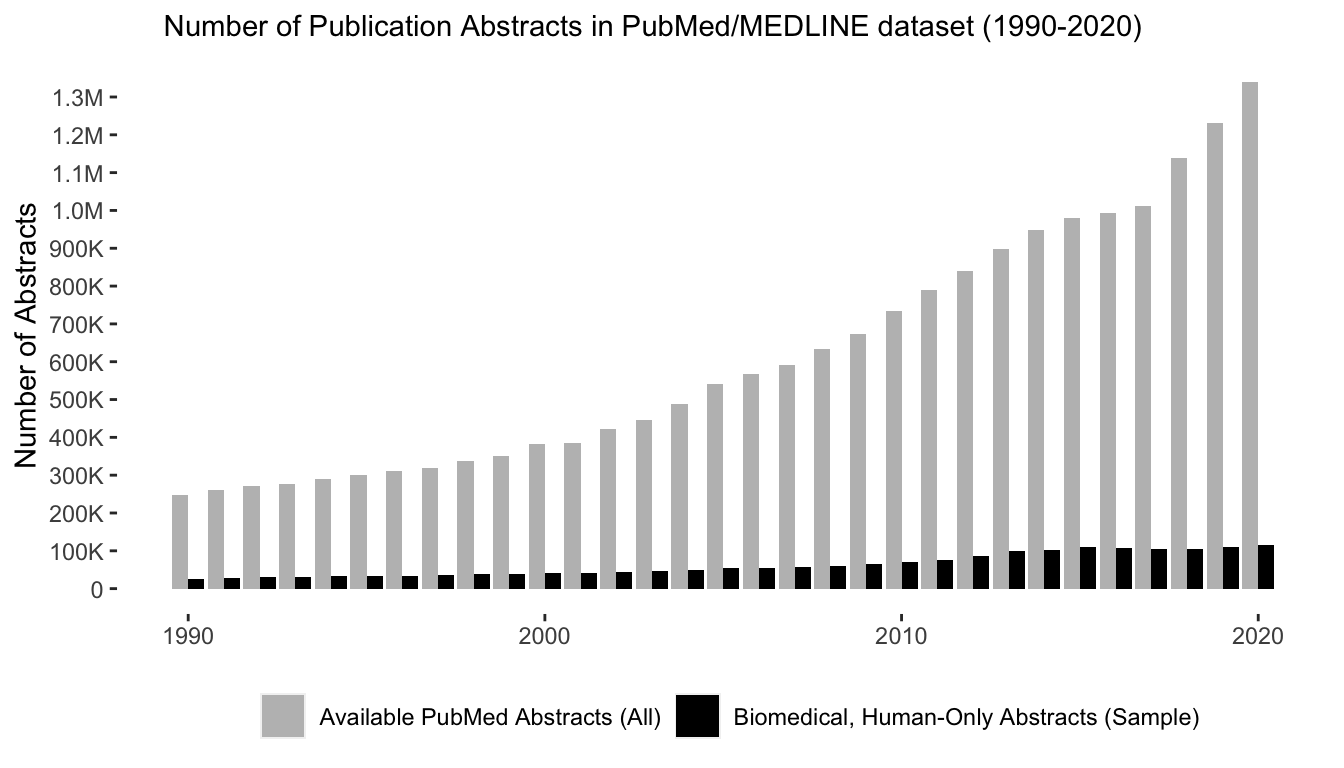

Our dataset derives from the PubMed/MEDLINE database – a free, publicly-available collection of more than 27 million scientific abstracts provided by the U.S. National Library of Medicine. After downloading the entirety of these data and building them up into a PostgreSQL database with the PubMed Portable package in Python, we narrowed our focus on the top journals in the field of biomedicine ranging from the years 1990 to 2020. To do this, we filtered our data to only include human-only research in 250 prominent biomedical journals based on Elseveir’s 2019 CiteScore rankings, leaving us with ~2.5 million abstracts. After aggregating these data, we conducted several pre-processing steps to standardize the data, including converting text to lower case, removing special characters and numbers, and transforming select compound and hyphenated terms to minimze false positive results on the terms we aimed to match.

While the specifics of each hypothesis test are detailed below, our overall analysis strategy depends on a “nested dictionary” approach to supervised text mining. This means that we created “dictionaries” with a number of “terms” that fall into “categories” for each hypothesis. We then used those dictionaries to count how often the terms in each category are mentioned within our corpus of abstracts. Although the magnitude of the data and reproducibility of the algorithms are useful for future research, we believe the potential utility of the dictionaries is what might help motivate future research on this topic. The dictionaries are by no means comprehensive, despite being predicated on past work, and could certainly benefit from continued scholarly debate, including from sociologists, bioethicists, and AI ethics scholars. To make these dictionaries as transparent as possible, we have detailed their construction below in addition to visualizing their hierarchical relations and providing searchable tables. We encourage any and all feedback about the best way to improve these dictionaries for future research, which can be shared via email in the top-right corner link.

Once all of our dictionaries were constructed, we ingested the data and used R’s tidytext package to unnest and count all of the terms in our corpus (both in raw counts and as proportions). The code for each hypothesis can be found on GitHub.

Hypothesis 1

For Hypothesis 1, our main goal was to examine the growth of the term diversity and its various metonyms, including cultural, disability, diversity, equity/justice, lifecourse, migration, minority, race/ethnicity, sex/gender, and sexuality. For each category, we manually compiled the terms based on our scholarly expertise in these fields and the likelihood of those terms being used to represent diversity in biomedicine. In the case of sex/gender and sexualties terms, we referenced the Oxford Dictionary of Gender Studies and, for the disability category, we also used the National Center on Disability and Justice’s Style Guide to inform term inclusion.

Our original lists were more comprehensive for some categories, but extensive sensitivity analyses of each category revealed that the inclusion of some terms yielded a substantial number of “false positive” results. For example, when we included “blind” in the disability category, but found that the majority of results returned related to “double-blind” studies, which are not indicative of the social diversity we are interested here. False-positive results were largely dealt with my removing terms that were too general to provide meaningful results or by reclassifying certain combinations of words during our preprocessing stage to minimize inflated count totals. This strategy proved effective in generating accurate results, which we validated by manually spot-checking a random sample of abstracts to ensure they are capturing valid mentions of the terms.

Perhaps, most importantly, the term “diversity” was a concept that took considerable effort to validate in our work. Diversity is a particularly polysemous term; it is has many meanings depending on the context. In fact, our research suggests that diversity rarely refers to issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion, but instead is much more commonly referring to heterogeneity, divergence, variation, complexity, or variability in biomedical research (see Word2Vec Results). Thus, we decided to include two categories: one with all mentions of diversity in addition to including all mentions of “social diversity.” The second category includes only mentions of diversity that co-occur in the same sentence alongside any of the other terms from the diversity categories in our first dictionary. To verify that this approach was meaningful and accurate, we took a random sample of 500 abstracts from the “all diversity” and 500 abstracts from the “social diversity” categories to manually validate that the terms fell into the appropriate category. Overall, we found that this approach was ~85% accurate in distinguishing between the two uses of diversity. For more on these tests, see the Hypothesis 1 Appendix page.

For those interested, the terms embedded within each category can be visualized by clicking on the collapsibleTree charts or by searching the interactive tables below.

Hypothesis 2

In the second set of analyses, we evaluate OMB Directive 15 and US Census categories. This coding process was similar to the one detailed above where we are compiling terms and then providing the raw and proportional counts of how often they are mentioned in the corpus. It is worth noting that sensitivity analyses were needed in this hypothesis - mainly to validate that “black” and “white” were being used to refer to populations rather than other contexts.

Hypothesis 3

In Hypothesis 3, we expanded the scope of our research project by examining the rise of population terms used in biomedical research. In their inductive analysis of population terms used in Nature Genetics, Panofsky and Bliss (2017) offer us a number of important insights about how to approach the task of collecting a census on these terms. First, these scholars note that researchers use population terms in ambiguous ways - using their polyvocality to enact population differences in genetic research. These scholars also note that continental, national, and directional terms are used increasingly more than racial and ethnic terms. Still, we are interested in getting an accurate count of each category and in order to do this we need a dictionary of terms to search on for each category. Although we did spend time searching for a comprehensive dictionary to serve our purposes, we were unable to find such a data source, especially of subnational, caste, and/or ethnic terms.

We ultimately decided to engage in an abductive data collection approach using Wikipedia as our primary source. Although the use of Wikipedia is not without its criticisms (Black 2008; Collier and Bear 2012; Kostakis 2010), the site is also among the top-15 websites used on the web (Alexa 2020), is subject to continuous peer review and editing, and is an active historical document that is crowdsourced by millions of online users (Wikipedia 2020). Thus, while the site is certainly subject to malicious and/or unqualified editing, it is also likely to be more comprehensive than any one single national governing apparatus that is subject to scrutiny by other political actors. As a reminder, our purpose in constructing a dictionary is not to create a hierarchical classification system or to aggregate (mis-)information about populations nor to classify them into strata. We largely circumvent such activities, noting how these terms have been used throughout the long history of scientific racism and other violent racialized activities. Instead, our goal is to aggregate a dictionary of the terms that scientists could use to enact population differences and create a census of how often these terms are used over time.

To compile this list, we first collected all of the relevant continental, subcontinental, and national terms from Wikipedia. Generating these lists was relatively straight-forward. Next, following Panofsky and Bliss (2017), we also collected terminology related to cardinal directions, terms from the Center of Disease Control Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Directive No. 15 and United States Census categories as well as terms related to (genetic) ancestry, race, and ethnicity. As a point of clarification, racial and ethnic terms refer simply to variations of “race” and “ethnicity” and not terms like black, white, asian, etc. When applicable, those terms fall under the OMB/US Census category sets.

In what proved to be the most complicated aspect of our curation process, we decided to collect all of the ethnic, tribal, and caste terms we could find from around the world and classify them under the umbrella category of “subnational.” This process began with a catalog of all indiginous peoples from around the world - a directory that was broken apart by continent. Next, we collected terms from pages that list populations from each continent:

- Africa , Asia, Europe, North America, South America, Oceania as well as their adjectival and demonymic forms.

Moreover, we drilled down to collect additional terms from the pages of smaller geographical units or large populations within each continent:

- Africa: Northern Africa, Eastern Africa, Northeastern Africa, Southeastern Africa, Western Africa, Southern Africa, Central Africa, the Bantu and Fula, African Pygmies peoples

- Asia: Middle East, Caucasus, Siberia, Eurasia, East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, Indian Caste, and Jewish ethnic terms

- Europe: All Terms Listed by Country

- North America: Arctic, Subarctic, First Nations, Pacific Northwest, Northwest Plateau, Great Plains, East Woodlands, Northeast Woodlands, Southeast Woodlands, Great Basin, California, American Southwest, Aridoamerica, Mesoamerica, Carribean, Central America, and Mexico

- South America: Peoples of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay, Venezuela

- Oceania: Australia, Austronesia, Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia

The point of this exercise was not to classify populations into any hierarchical category. In fact, we explicitly chose to create the umbrella term “subnational” to circumvent further contributing to the violent history of hierarchical classification into races, classes, or castes. Instead, this process was meant to compile the largest, most inclusive list of population terms we could logically manage - knowing that this list will likely never be exhaustive because the enactment of population differences depends on ambiguity, polyvocality, and dynamism. In total, our list includes more than 6,600 terms. In addition to visualizing these terms in the collapsibleTrees below, you can also search through the interactive table.

Hypothesis 4

To test Hypothesis 4, we used Python’s gensim package to examine how semantically similar the terms related to race, ethnicity, and diversity are in PubMed abstracts and compare how their semantic similarity changes over time using two word embedding models. To do this, we ingested the human-only abstracts from the 250 biomedical journals using all of the 1990-2000 abstracts (n = 430,551) and all of 2010-2020 abstracts to ensure both models were trained on datasets of the same size (n = 1,131,646). Next, we converted the text to lowercase, removed punctuation, numbers, digits, white space and stopwords, and then lemmatized to remove inflectional word endings. We then trained a Word2Vec model for each time period with words mentioned less than 5 times being removed from the model, the skip gram window set at 5, a vector dimensionality of 256, and the iterations set at 5. To compare these models over time, we aligned these vector spaces using an orthogonal procrustes correction akin to that used by Hamilton (2016). We then obtained the “cosine similarity” score, or the cosine of the angle between two word vectors, to determine how semantically similar select word vectors were within each time period and how they changed over time.

One of the primary limitations of Word2Vec models is that they are not able to account for the multiple uses of polysemous words. As we demonstrate in H1, “social” uses of diversity constitute only a small subset of more general uses of diversity, which we suspected could impact our results. Thus, we developed a procedure to convert all mentions of diversity that were classified as “social diversity” with our classification algorithm from H1, replacing them with the distinct string of “socialdiversity” before training new Word2Vec models on each of the 1990-2000 and 2010-2020 samples using the same parameters as the baseline models. This process treats the social diversity token as a distinct vector while leaving other mentions of diversity entirely unencumbered. Below, we refer to the comparisons of our baseline models as the “unparsed” models while the comparisons that differentiate diversity from social diversity are referred to as the “parsed” models.

After these models were trained, we extracted the most similar word vectors to race, ethnicity, diversity, and social diversity to understand which vectors are commonly used in the same contexts. Second, we compared the race, ethnicity, and diversity vectors to one another within the 1990-2000 and 2010-2020 models. These comparisons yield a cosine similarity score that can be interpreted like a regression coefficient where a value of 1 means that two words have a perfect relationship; 0 means the two words have no relationship; and -1 means they are opposites. We then subtracted the latter model’s cosine similarity score between each combination of vectors (e.g. diversity and race in 2000-2010) from the baseline (e.g. diversity and race in 1990-2000) to understand how the relationship changed over time. Here, negative outcomes mean that the word vectors become more dissimilar over time while positive outcomes mean word vectors are more similar in the 2000-2010 model. Using a similar strategy, we examined all of the word vectors within the H1 and H3 categories, compared them to the diversity vector to acquire their cosine similarity score, averaged these coefficients within each category across the models, and subtracted the latter model’s score from the baseline model. These results tell us whether diversity has become more or less semantically similar to these categories over time.

For our main findings, please check out our Results page and for methodological questions, please feel free to contact us at the email in the top right corner of this page.

Appendix

One of our main goals was to improve the accuracy of our results and one of the ways that we did this was to exclude studies that were conducted on animals. Below is the list of animal terms we used to exclude studies. While still not comprehensive, the list does include 1,124 terms that we eventually plan to formalize into a function for other computational social science researchers.